Joining the dark side of the Force for a week

Hello! I am Clemens, a postdoc at the University of Cambridge, and in this #RealTimeChemInFocus blog post you will follow me, a chemist, doing some “biology” a.k.a. the dark side of the Force.

I know it’s weird. Why would a chemist venture into the world of biology in the first place? Honestly, it just happened! Organic chemistry was my first love as an undergrad, even after my final product of a 9-step carbohydrate synthesis decided to spontaneously decompose! I still try holding on to my first love by attempting to solve the Denksport problems of Dirk Trauner’s group and I still admire elegant total syntheses. However, the dark side of the Force has always been strong in me and over the course of my PhD and postdoc, I gradually moved towards chemical biology. I can’t help it; I am simply fascinated how chemistry can give answers to complex problems by probing or perturbing cellular systems. So, without further ado, this is a typical week in my life.

Monday

Although I am not a particular fan of Monday mornings, this Monday morning is one of the toughest of the year! I just came back from an exciting week featuring the ISACS16 conference in Zurich and a 3-day music festival in Austria (Figure 1). It made me realize how similar festivals and conferences are. Long days, short nights, meeting new people and listening to some raw talent all day long.

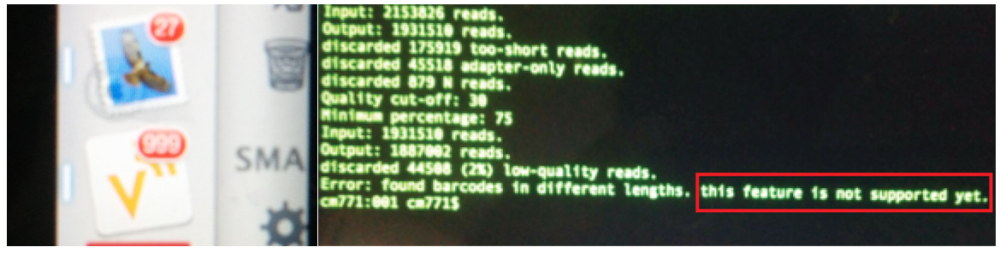

Don’t get me wrong, I enjoyed it a lot, but it took a lot of energy out of me and getting up for the obligatory Monday morning group meeting at 9 a.m. is tough. I get coffee and arrive on time, a miracle! After the meeting, which is held in the Chemistry department, I postpone my plans to go to the Cancer Research UK (CRUK) Cambridge Institute, where the biology projects of our group happen, for one day and take some time to recover. After all, I missed a lot of science in the last week, as my RSS feed and email client tell me (Figure 2). Even better, I have to analyze some exciting sequencing data, which were generated in my absence. Having multiple, diverse projects running in parallel is one of the great things about being a chemical biologist. As my computer does all the hard work, aligning millions of reads to a reference genome, all I need to do is drink coffee and use the software correctly. The latter is something I am still struggling with (Figure 2). Nevertheless, at the end of the day I get everything analyzed and the results tell me that I am all set for writing my first manuscript as a postdoc! I also managed to catch up with my emails and the RSS feed so it’s time to cycle home and get some much-needed rest!

Tuesday

Another morning and it is time to head to the CRUK Cambridge Institute (Figure 3), where I will spend the rest of my working week.

I am not sure how many of you fellow chemists have ever set food in a hardcore biology working environment, so let me give you a short tour. Things here are a lot cleaner and the number of fume hoods is sadly kept to a bare minimum. They are mostly used for “dangerous” phenol-chloroform extractions of nucleic acids. Being thrown into a new working environment, I always look out for things I recognize or can relate to. Lab coats are mandatory and even wearing eye protection is reinforced (Figure 4). You can also spot the occasional TLC chamber (everybody loves TLC chambers), although they are often used for a completely different purpose than analyzing your reactions.

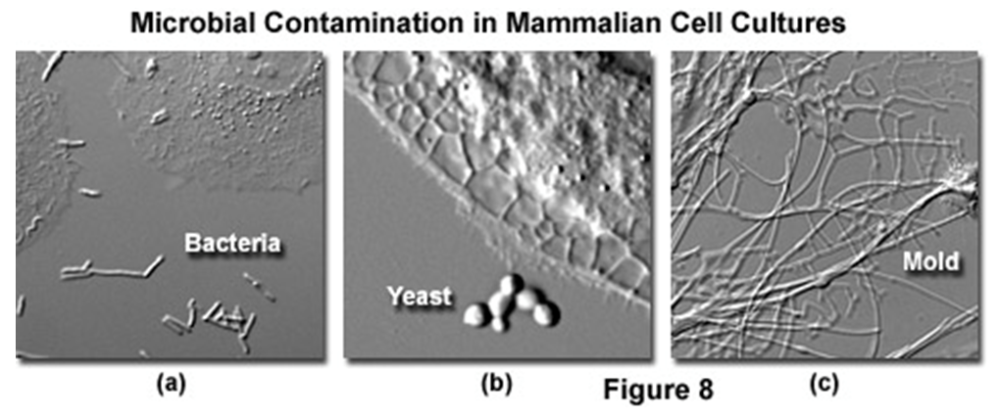

Once you are feeling more comfortable in the world of biology, you might even find more similarities to your familiar chemistry lab. For working with tissue cultures, we have special hoods that remind me a lot of glove boxes. Instead of using an airlock you are using ethanol to decontaminate everything before placing it inside the hood. Of course, once you put your thoroughly washed hands inside, your nose starts to itch. Another similarity to the familiar glove box; you have to keep the place spotless as contamination with evil bacteria or yeast will spoil not only your cells, but could affect the cultures of a whole lot of other people (Figure 5). This scenario is especially bothersome, when you have worked for months creating a cell line for a particular disease you’re studying, only to find it contaminated and yourself right back at the start of your project.

Figure 5: Things you do not want find in your mammalian cell cultures! (https://www.microscopyu.com/articles/livecellimaging/livecellmaintenance.html)

Unfortunately for you, I won’t culture any cells this week, so I can’t show of my recently acquired and still embarrassingly clumsy skills, but I encourage anyone who’s curious to give it a go. It is surprisingly simple to culture mammalian cells like HeLa or HEK293 and as a chemist you have enough skills in your repertoire to learn it quickly. Because you have to work carefully and be gentle with the cells, I always picture myself handling tert-BuLi, which freaks me out, but my cells seem to appreciate the gentle treatment.

The plan for the week is to continue with a project I stopped working on before my week abroad. To cut a rather long story short, we identified some potential protein targets in a screen and are now keen on validating these hits. To get an independent confirmation, we need to clone all 28 proteins of interest (P.O.I.) into a transfection vector and express them inside the cell as a tagged version, in order to confirm the interaction by Western blot. That should suffice to give you a rough idea, and the rest of my day is spent planning everything and diluting 56 primers to the right concentrations. By the time night falls, my pipetting thumb has had a good workout!

Wednesday

I spent my PhD in an enzyme-engineering lab, so I did my fair share of cloning and from my experience I can tell you everything starts approximately like this:

Figure 6: Every good cloning starts with a successful PCR. The tricky thing is where to go from there.

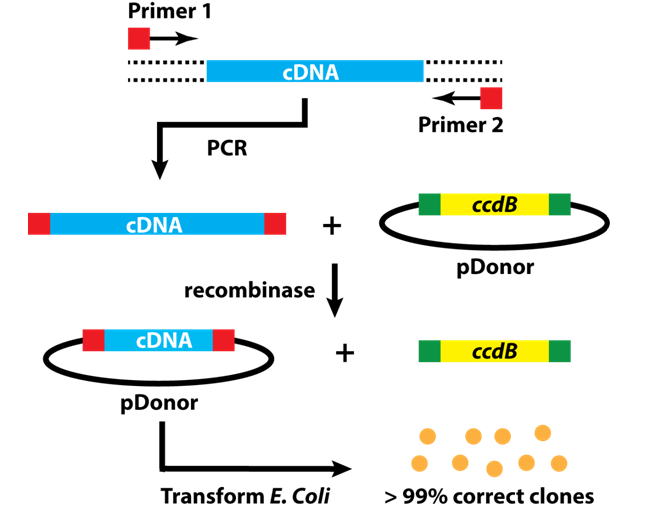

For the current task at hand it is a bit trickier. For half of our P.O.I.s we were lucky and could obtain the cDNA – that is the complementary DNA synthesized from the corresponding messenger RNA – in the form of E. coli glycerol stocks that carry a vector containing the cDNA. For these proteins, cloning is easy: isolate the plasmid from the E. coli precultures and simply amplify the cDNA with the correct primers. We use primers that have 5’ and 3’ overhangs, which allow us to subclone the amplified cDNAs into the Gateway cloning system (Figure 7, http://scienceftw.wikia.com/wiki/Gateway_cloning).

This method is neat, because it uses a recombinase instead of restriction enzymes and the main objective is to bring your insert into the entry vector for the Gateway system. From there, you can use another recombinase and insert your cDNA into a whole bunch of different vectors that carry appropriate tags and also allows transfecting mammalian cells! Compared to 10 years ago, when I first tackled a cloning problem, this protocol is a piece of cake.

As I started the E. coli precultures from the glycerol stocks before I left yesterday, my day consists of isolating the plasmid, doing the PCR reactions, and purifying the inserts. Sounds like a walk in the park, but it takes time (a lot of pipetting again). By the end of the day, I got 12 out of 28 cDNAs ready to insert them into the entry vector. It was clearly a successful day and I leave the lab happy for my weekly basketball game!

Thursday

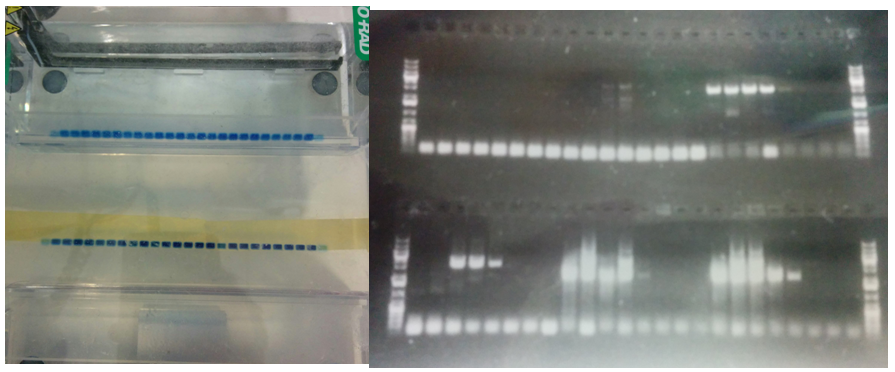

Today, I start the cloning of the P.O.I.s we couldn’t obtain from the cDNA in the convenient E. coli glycerol stock form. This cloning is a lot trickier, as we have to prepare our own cDNA. For this, we isolate the total RNA from HeLA cells, which involves a phenol-chloroform extraction (so dangerous!) in a real hood (so happy!). Next, we use a poly dT primer that – at least in theory – is expected to hybridize with all mRNAs in the cell as they carry a complementary poly A tail. Creating an RNA-DNA duplex allows us to reverse transcribe the whole transcriptome and generate our sought-after cDNAs. In principle, we should have our P.O.I. cDNAs in there as well, however there is no easy way of determining the concentration and whether they were fully reverse transcribed in the first place. Nevertheless, we take the crude reaction as a template for some PCR reactions. Given that we are working with a complex mixture, I start a gradient PCR – which probes annealing temperatures between 50 and 70 degrees – and hope for the best. A few hours later, I load the first 48 out of 96 PCR reactions onto an agarose gel (Figure 8), and after size separation take a look at the gel under UV light! Hurray, for 4 of 6 targets we amplified something (Figure 8). I check, whether they have the right size, which they all do, and purify them. The second batch looks equally good, which means that combined with the inserts I amplified yesterday, I got 25 out of 28 constructs ready for the recombination reaction. That’s pretty awesome and I call it a day!

Friday

It’s Friday! And it’s a special Friday, as we are invited to our bosses place for a British “summer” BBQ. I prepared some salmon-spinach roles yesterday night, but they really looked ugly so I didn’t dare taking a picture. With the BBQ coming up later in the afternoon, it will also be a short day in the lab, which suits me, as all I need to do is finishing the first stage of my cloning efforts.

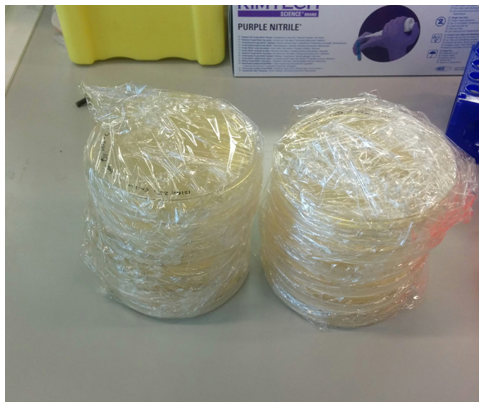

To insert my cDNAs into the Gateway entry vector, all I need to do is mix the vector with my PCR products. I then add the recombinase enzyme that swaps the standard insert – a gene encoding for a toxic protein that prevents growth of false positives – with my cDNAs. After incubating the reaction for an hour at room temperature, I thaw some chemically competent E. coli cells, which I will use for the upcoming transformation. These bacteria are suspended in a buffer-DMSO mixture, conditions that promote plasmid uptake through the cell membrane when heated to 42 degrees Celsius for a short time (about a minute). This procedure is a bit cruel as it kills most of the bacteria; after all they don’t like the DMSO too much. However, some bacteria that took up the plasmid during the heat shock survive and they are allowed to recover at 37 degrees Celsius in a rich medium for half an hour. Next, they are pelleted by centrifugation and resuspended in 100 μL of medium. The E. coli suspension is finally spread onto LB agar plates that have the right antibiotic (kanamycin) in them, which ensures the plasmid is amplified while the bacteria happily divide. Normally, you would incubate at 37 degrees Celsius overnight, which will give you good-sized colonies; however, with the BBQ and the weekend coming up, I just place them on my bench, where they will incubate at room temperature over the weekend, delaying the growth by about two days (Figure 9).

All there’s left to do: Head home, get the ugly salmon-spinach roles out of the fridge, cycle to my bosses place and enjoy a burger and some beer at the BBQ. Obviously, rain begins to fall as soon as the BBQ starts, but hey, that’s life in the UK after all.

Author biography:

Clemens Mayer is a postdoc, working at the University of Cambridge under the supervision of Prof. Shankar Balasubramanian. He was born in Graz, where he completed his undergrad in 2008. Subsequently, he moved to Zurich to pursue his Ph.D. in the field of enzyme engineering. In 2014 he joined the University of Cambridge, where he is currently investigating the role of RNA structures in biological processes. Passions include coffee, basketball, the accumulation of useless knowledge, being a geek, and dreading the English summer.

Clemens Mayer is a postdoc, working at the University of Cambridge under the supervision of Prof. Shankar Balasubramanian. He was born in Graz, where he completed his undergrad in 2008. Subsequently, he moved to Zurich to pursue his Ph.D. in the field of enzyme engineering. In 2014 he joined the University of Cambridge, where he is currently investigating the role of RNA structures in biological processes. Passions include coffee, basketball, the accumulation of useless knowledge, being a geek, and dreading the English summer.